What Have I Done?

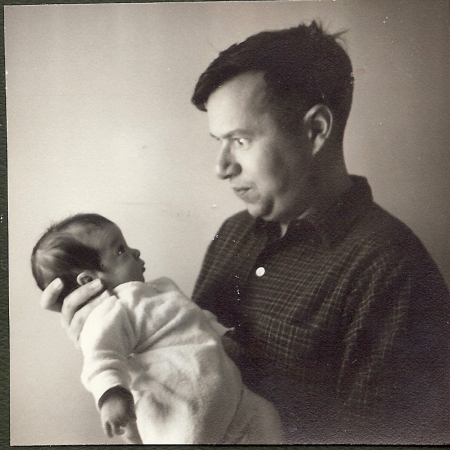

This is a picture of my father, Henry Ebel, holding me, Kathy Ebel.

Check out the look in his eyes. Those are crazy eyes, am I right? He’s glaring at me, for God’s sakes. He doesn’t know who I am or how I got there or what he did to deserve it or what the fuck he’s supposed to do about it now.

In 1970, two years after this picture was taken, my father splits. I see him occasionally until I am seven years old, and then it’s Radio Silence for the next 19 years, until I meet him again when I’m 26.

He died in 2009.

I wasn’t mentioned in his will.

By which I don’t mean “Boo-hoo, my father passed away and I got bupkus.” He didn’t acknowledge me as a next of kin whatsoever, I’m just saying is all. These facts support my interpretation of this image. The first time I see this picture, I see it one way only. I’m convinced it reveals a unique emotional truth. And also, that it predicts the future.

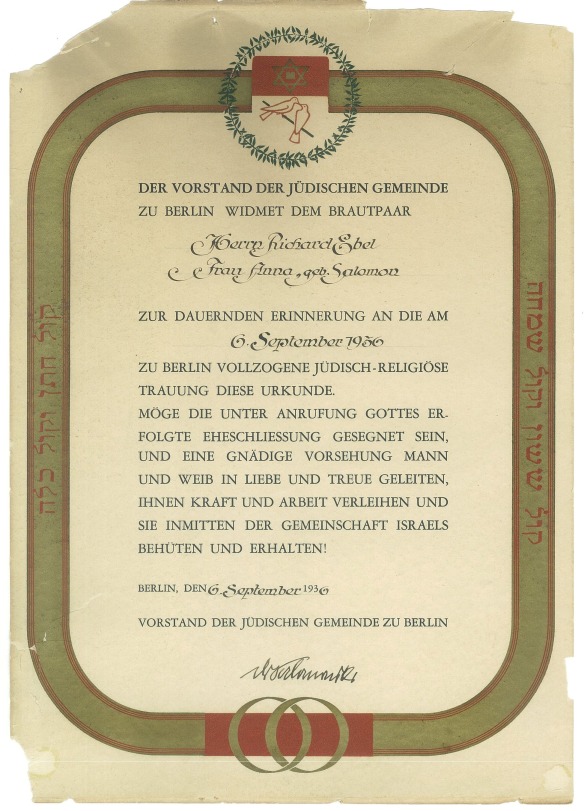

My father was born in Berlin in 1938. He lived at Iranische Strasse 2. He fled Germany, with my grandparents and his older brother, about a year later. I know only the bullet-points of my father’s life, a generational combo-platter: Morningside Heights, Stuyvesant High School, Columbia, phi beta kappa, Ph.D, LSD, primal scream therapy.

Sure, none of us knows our fathers. But I really didn’t know mine. So from these shreds – a little ‘Punch” magazine here, a little Constant Comment tea there, a fringed suede jacket, the cover of Sgt. Pepper — I’ve hallucinated a ghostly person and a flimsy story, filtered through my hyperactive imagination, influenced by my chaotic childhood in and around New York City in the 1970’s and 80’s. I know much more about my mother’s immigrant story, and since she raised me, I’ve inflated her mythology to fill the gap left by my father’s absence. I’ve told myself I don’t really have a father, which has been easier to digest than the shards he left behind. Add a couple of decades of living on the hallucinatory fumes of this concoction and the result is a deep sense of personal disorientation.

And then one day, several months after my father’s death, I’m sitting in Video Village, the cluster of captain’s chairs arranged around a pair of monitors on a dusty, cavernous Warner Brothers sound stage in Burbank, California.

This is the set of the CBS cop show COLD CASE, where I am a staff writer overseeing my first episode for the series. The story is about the murder of a young Russian opera star whose family defects to the United States just before the fall of the Berlin Wall. She’s hot, she’s got pipes, she wants to sing American rock and roll, not the opera for which she’s been trained in a Soviet conservatory. Rejecting her father? Bucking the system? Determined to express her own voice?

It’s clear the bitch must die.

I am deep in conversation with a visiting director about something else entirely. I’m going to call him Casper Fleming. (This is not his real name.)

Casper, a talented theater and film director breaking into TV, is shadowing the director-for-hire for the duration of the shoot, and we hit it off immediately. There is something rushed and breathless about our chemistry. It’s the transplanted New Yorker thing, it’s I’m-gay-you’re-straight-let’s-fall-in-love, it’s what-are-we-doing-on-the-set-of-a-Bruckheimer-cop-show-when-we’re-both-supposed-to-be-starring-in-a-revival-of-Company. Casper and I rapidly construct a pile-up of personal and pop-cultural references and nimbly climb it. From the top, we survey a landscape of Sondheim lyrics, Paul Smith glasses frames, last week’s New Yorker cover, obsession with the presidential election, white anchovies, tooth bleaching, Gucci horse-bit loafers, our careers, and the offerings at craft services. Into this mix we gleefully add parallel tales of nightclubs visited in lower Manhattan between 1986 and 1992, and the freewheeling assembly of People We Have In Common that I refer to as Jewish Geography.

But when we realize that we are both First Generation, his father from Italy, mine from Germany, that’s when our bond is Crazy Glued. Of course Casper and I are destined to be here now, to change one another’s lives.

“You know,” Casper advises me, “you could probably apply for German citizenship. That’s what I did with Italy, and now I have my E.U. passport. It came in wonderfully handy when I was shooting my costume drama there.”

German citizenship.

E.U. passport.

Wonderfully handy.

So I start to poke around. And I find out about Article 116 par. 2 of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (Grundgesetz). It goes something like this:

“Former German citizens who between January 30, 1933 and May 8, 1945 were deprived of their citizenship on political, racial, or religious grounds, and their descendants, shall on application have their citizenship restored.”

I decide to scrape up whatever documentation about my father and his family’s flight from Germany that I can.

I decide to see if Germany will have me back.

And this blog will monitor my progress.

At first, I think I won’t have anything to say, this experiment won’t count, unless the German government opens its pale, muscled arms to me. Then I’ll move to Berlin with my family for a year or two to write a book about being the New Jewess in town. We’ll live in the Turkish quarter, become experts on the hip-hop scene, our son will go to the International School, he’ll make terrific new friends with villas in Croatia, and memories of Bed, Bath and Beyond will fade from his mind. I’ll get a job doing something for somebody, the heels of my pumps will click urgently on cobblestones slick with a November rain as I wrap my Burberry trench tighter against the chill of the evening and hurry home from the metro through pools of lamplight to our flat, a brown paper package of sausages and a Herald Tribune under my arm…shit, we might never even come back.

But then I realize, shit. They might not want me back.

The Federal Republic of Germany might hold me at arm’s length, flashing those crazy eyes. “Who are you?” they might say. “How did you get here?” “What did we do to deserve this?” “What are we supposed to do about this now?”

But if I wait to have a story worth telling, I might miss the story I am standing in right now, in the middle of my life, at the edge of the country, in the foreign city I already live in.

Welcome to Fatherland.